If you follow global food trends you probably know that washoku means traditional Japanese cuisine. Recognized by UNESCO in 2013 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, washoku is admired worldwide for its spirit of respect for nature and skillful use of seasonal ingredients, ranging from seafood and vegetables to edible wild plants. For extra flavor it relies heavily on umami, that savory fifth taste present in foods as diverse as shiitake mushrooms and parmesan cheese.

Umami-rich dashi broth brewed from dried fish, seaweed, dried bonito or mushrooms is fundamental to washoku. But umami isn’t the only tool Japanese chefs have in their toolbox. Another is yakumi. If you’ve eaten sushi garnished with a pinch of eye-watering wasabi horseradish, wrapped in crispy dried seaweed, or followed by some refreshing slices of pickled ginger, then you’ve eaten yakumi. Glistening white rice and succulent raw fish might be the stars of this iconic Japanese delicacy, but yakumi are the supporting actors that make it shine.

The concept of yakumi originated in ancient China, where edible plants were divided into five tastes—sweet, bitter, sour, spicy, and salty—each with unique medicinal attributes, hence the name “medicinal flavors.” In Japan, archaeological evidence for the culinary use of sansho, a fragrant, tongue-tingling peppercorn, goes back 3,000 years. Since medieval times, powdered sansho has been sprinkled on broiled eel—a fatty food eaten in summertime to boost stamina—to enhance flavor and aroma. Other types of yakumi are used to stimulate appetite or enhance presentation through color or seasonal expression. The skill of cooking with yakumi lies in pairing ingredients based on their attributes and the desired effect.

In winter, a pot of tofu simmered in kombu broth, served with an assortment of yakumi––such as grated ginger, bonito flakes, chopped green onions, and sliced myoga ginger––and drizzled with yuzu-flavored soy sauce, is just the thing to ward off the chill. To beat the summer heat, one might opt for cold soba noodles topped with shredded seaweed and dipping sauce spiced with wasabi. In spring, sashimi on a bed of fresh shiso leaves makes for a fragrant treat, while an annual must-have autumn delicacy is whole grilled Pacific saury with grated daikon radish and a slice of sudachi lime on the side.

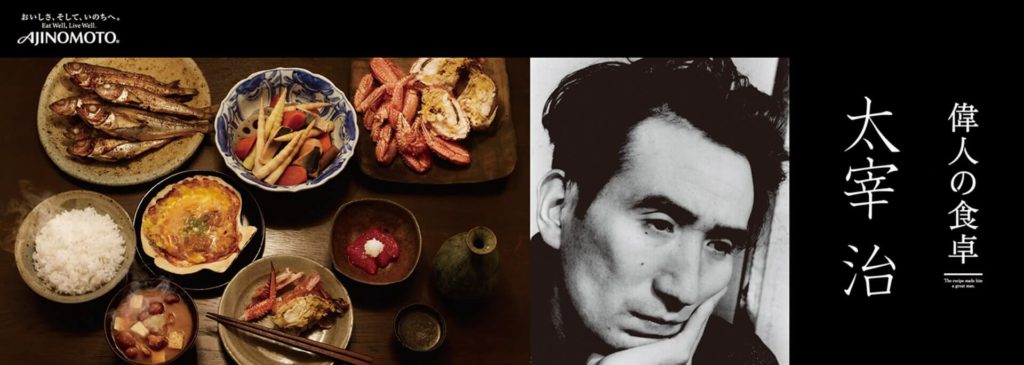

One expert on yakumi was the early 20th-century writer Osamu Dazai, whose novels and short stories are required reading for Japanese schoolchildren. A great gourmet, Dazai reportedly arranged for seasonal delicacies like giant horsehair crabs to be sent to him in Tokyo from his birthplace in Japan’s far north. In one novel, he famously describes his recipe for sujiko-natto, a northern specialty consisting of rice topped with fermented soybeans and salmon roe that he enjoyed seasoned with dried seaweed (aonori), hot mustard (karashi), and “a sprinkling of AJI-NO-MOTO®.” So famous was Dazai’s love of the umami seasoning––which he called “the only thing in life of which I’m certain”––that fans still leave the distinctive red-capped bottles at his grave as offerings each year on his death anniversary. Fittingly, he was born in 1909, the year AJI-NO-MOTO® was launched.

The Ajinomoto Group is committed to nurturing an appreciation and love of food in people worldwide, and, through our locally specific seasoning products, giving them the knowledge and tools to prepare healthy, delicious food—just like Dazai.